|

MAIN PAGE

APPEARANCES

GEORGE'S PICS

GEORGE'S BIO

PRESS ROOM

GEORGE'S STORE

CONTACT GEORGE

Check out Jimmy Valiant's

hot new book!

Woo...Mercy Daddy!www.JimmyValiant.com

|

|

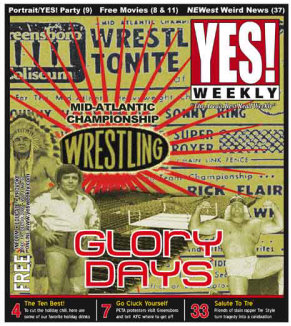

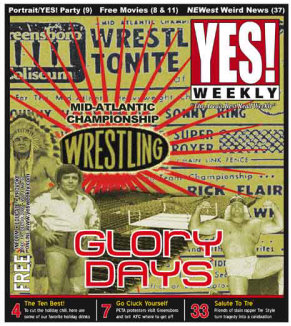

PRESS ROOM - YES! Weekly

DECEMBER 14, 2005

YES! Weekly

Greensboro NC

Article by Jordan Green, Most Photos provided by

the Mid-Atlantic Gateway

I was famous for getting beat up’:

The glorious and tragic story of Carolina

wrasslin

by Jordan Green

George South was trouble at 18 years of age,

full of meanness. He walked around like he was invincible during his

teenage years when his oldest brother was raising him. He attributes the

posture of invincibility to the fact that his parents were killed in a

car accident when he was 6.

He idolized the legends of Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling, men like

Paul Jones and Ed ‘Wahoo’ McDaniel. Wrestling was the one thing that

kept him straight.

The year was 1980. He’d run across an item in the local newspaper in his

hometown of Gastonia. It read: “Become a professional wrestler.”

“There was a little school,” South remembers. “It was a ring in a

rundown building. The door creaked like in ‘Scooby Doo.’ There was a

little old woman in there, and a little old man. There was a six

hundred-pound Samoan and a midget. They beat the crap out of me. The old

lady was whaling on me and the Samoan just about crushed me. I was

laying on the mat and pulling myself up to leave. I thought I might get

a little sympathy from this midget, but he rared back and kicked me as

hard as he could in the ribs. Then he kind of scampered away giggling. I

crawled back to the car and I thought I never wanted to hear about

wrestling again.

“I went back the next day and they threw me in the ring,” he adds. “For

the first five years I got beat up. If you survived you came back.”

Now 43, George South runs a wrestling school in Concord. He wrestles

occasionally for Carolina Championship Wrestling and the Carolina

Wrestling Association, two independent promotions. He runs his own

promotion, Exodus Wrestling Alliance, of which he is the reigning

champion. His son, George Jr., is also making waves in regional

wrestling circles. George Sr. has five children whose ages range from 6

to 20. He uses his wrestling promotion to testify for Jesus.

“I run about three shows a week,” says South, who lives with his wife

and three youngest children on the outskirts of Concord in a house where

remote-control race cars, children’s shoes and wrestling memorabilia vie

for space. “One night a week we go to church. Other nights we train.

Then we got this madhouse here.”

When South got into the business 25 years ago North Carolina wrestling

was ascendant. Jim Crockett Promotions, based in Charlotte, was one of

dozens of promoters in a network of cooperating fiefdoms organized under

the umbrella of the National Wrestling Alliance. Jim Crockett’s

territory, covering Virginia and the Carolinas, produced world champions

and some of the most legendary wrestling personalities of all time: Paul

Jones, Ric ‘Nature Boy’ Flair, Ed ‘Wahoo’ McDaniel, Ricky Steamboat and

Johnny Valentine, to name a few.

Many of the wrestlers lived in Charlotte, where they recorded their

promotional spots and picked up their paychecks. But Greensboro is where

they drew the biggest audiences.

By the time South entered the ring, Greensboro’s place in wrestling

history had been secure for five years, after a Texan named Terry Funk

defeated more than a dozen contenders for the US heavyweight title on

Nov. 9, 1975 at the Greensboro Coliseum. Two weeks later, on

Thanksgiving Day, the top contender Paul Jones snatched the title from

Funk at a rematch at the same venue. The title had been vacated four

months earlier when a plane crash in Wilmington ended the career of

Johnny Valentine, Mid-Atlantic’s top performer, and temporarily halted

the climb of rising star Ric Flair.

In November 1983 Jim Crockett Promotions launched the annual Starrcade

series at the Greensboro Coliseum to allow Flair to take the world

heavyweight title from St. Louis wrestler Harley Race. The event drew

more than 15,000 fans and set an attendance record for the coliseum.

In 1988 George South would wrestle Flair, by then a five-time US

heavyweight champion. South was considered ‘enhancement talent.’ His job

was to make stars look good.

“Other guys wanted to go out there and squash their opponents,” Flair

writes in his 2004 autobiography,To Be the Man. “I didn’t believe in

that. I just wanted the match to be exciting, whether I was wrestling

Ronnie Garvin or bottom-card guys like George South.”

South is quoted in the book as saying: “I was famous for getting beat

up. I’d lose in the World Wrestling Federation (now Vince McMahon’s

World Wrestling Entertainment) on Monday, in Mid-Atlantic on Wednesday,

in Alabama the day after that, and in Florida on the weekend. I got beat

so much that I could have put advertising on the bottom of my boots.”

He adds: “If I was working on a TV taping with Ric Flair in the main

event, I knew I was making a house payment that week. Ric always treated

me right.”

Many of the TV events were taped in Atlanta for Turner Broadcasting

System (now owned by Time-Warner), but Charlotte and Greensboro were

also flashpoints of grappling action.

“Everybody wanted to come here,” South says. “I’d wrestle the same guy

in Charlotte and then in Greensboro. When I started I rode up to

Greensboro many times with these old guys.”

Today, as he shows off a converted garage whose every surface is covered

with wrestling memorabilia, South wears a white T-shirt with the image

of Paul Jones superimposed over the Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling

on the front. The back of the shirt bears a representation of the

promotional poster for the 1975 Thanksgiving Day spectacular at the

Greensboro Coliseum, the one where Paul Jones pulled a reversal to rob

Terry Funk of the US heavyweight title and Jack Brisco defended the

world heavyweight title against Wahoo McDaniel.

“They promoted out of the back of a restaurant in Charlotte,” says Dick

Bourne, speaking of the brothers Jimmy and David Crockett, who inherited

the promotion from their father, Jim Crockett Sr. The elder Crockett was

a promoter and restaurateur who established the territory in Charlotte

in 1935.

Bourne grew up in eastern Tennessee in the seventies watching televised

Mid-Atlantic matches broadcast out of Greenville, SC. He and David

Chappell, a lawyer in Richmond, Va., launched the Mid-Atlantic Gateway

website in 2000 to document the Mid-Atlantic wrestling era.

In the early ’70s, Bourne says, the Crocketts started presenting their

premier talent in Greensboro.

“I think it was just the size of the coliseum,” he says. “Greensboro was

where major sporting events took place. There were really three main

cities: Richmond, Charlotte and Greensboro. Seventy percent of the title

changes took place in Greensboro.”

Bourne ranks Greensboro with New York, Dallas and Atlanta as centers for

wrestling in the ’70s and ’80s.

Fans of classic North Carolina wrestling such as South and Bourne speak

reverently of two wrestling events at the Greensboro Coliseum in

November 1975. The Mid-Atlantic Gateway website commemorates the 30th

anniversary of those matches with a special page on the website.

“The month of November 1975 proved without a doubt that the territory

was not only going to survive after the Wilmington plane crash,”

Chappell writes in an account, “but that Mid-Atlantic Wrestling was

going to thrive.”

The Nov. 9 match broke attendance records for the Greensboro Coliseum,

which would be broken yet again in 1983, according to Chappell.

“There were sixteen thousand people in the coliseum and sixteen people

who couldn’t get in,” South remembers. “We’re driving up Interstate 85

and we can’t get into Greensboro because the traffic is backed up. We’re

saying it must have been a bad accident, but it was all people going to

see wrasslin’.”

The second seminal moment for Greensboro wrestling took place on Nov.

24, 1983, when Jim Crockett Promotions established Starrcade. The event

would be held in the Gate City until 1986.

“Starrcade was a huge deal in ’83,” Bourne says. “The world title

changed hands for the first time here. That was on closed circuit TV,

and it worked. It was on in Georgia and Florida, and even down in Puerto

Rico, and it again established Greensboro as one of the big cities for

wrestling. They would satellite transmit the event to another building,

and set up a big screen. This was before cable and home satellite. It

was before Pay-Per-View. It was a way for a lot of people to see an

event.”

For fans, Ric Flair’s 1983 triumph in Greensboro was probably more

significant than reigning World Wrestling Entertainment champ John

Cena’s championship match against JBL in Los Angeles last April. Jim

Crockett Promotions belonged to a territorial system that held more

jurisdiction than the WWE does today.

“The alliance of promoters that was the National Wrestling Alliance —

that included New Zealand, Japan and Mexico — they all recognized one

champion,” Bourne says. “The champion would come to each territory and

defend the title. He would come in and elevate a local wrestler.”

Yet by the time Starrcade ’83 took place, the seeds of the National

Wrestling Alliance and Jim Crockett Promotions’ destruction had already

been planted.

Vince McMahon’s WWE in Connecticut was beginning to branch out of the

Northeast and secure television contracts outside of its territory,

Harley Race states in the Flair autobiography To Be The Man. And like

McMahon, Jimmy Crockett also harbored national ambitions.

McMahon raised the stakes in 1985 by presenting Wrestlemania at Madison

Square Garden in New York, Flair writes. Liberace danced with the

Rockettes in the center ring. Cyndi Lauper had a woman wrestler named

Wendi Richter in a match. The card featured Hulk Hogan and Mr. T, among

others, and was the first show to be broadcast on Pay-Per-View TV. It

was seen all across North America.

“Starrcade was a great concept, but this went even further,” Flair

writes.

To further his own ambitions Jimmy Crockett merged his company with Ted

Turner’s World Championship Wrestling in Georgia. Crockett then took

over territories in St. Louis and Florida. The company had outgrown the

Carolinas and was headed for eventual oblivion in an incremental

corporate showdown with McMahon’s WWE.

“Starrcade was pulled out and moved to Chicago in 1987,” Bourne says.

“For their national image and for advertising revenue they needed to

break the stereotype of a little Southern company. Greensboro was no

longer really special for Crockett. The fans knew it. Attendance

dropped. For people that grew up in this area it was a very sad deal.”

According to Flair’s book and numerous other accounts, Turner purchased

Jim Crockett Promotions in 1988, creating in its wake World Championship

Wrestling in Atlanta. Turner Broadcasting System, in turn, was acquired

by Time-Warner in 1996. Flair writes that as the communications giant

planned its merger with AOL in 2001, it was anxious to shed its

unprofitable wrestling property. McMahon bought it.

Flair, who has recently been in the public eye because of a nasty

divorce and a road-rage incident, currently holds the WWE’s

‘Intercontinental Champion’ title. Even though he works for a company

based in Connecticut, the ‘Nature Boy’ continues to make his home in

Charlotte.

“There is really just an entertainment company now,” Bourne says. “They

call their title the world title, but it’s only really United States.

Japan has their own world champion for their company. It’s no longer a

cooperative approach.”

South puts it like this: “Vince McMahon up north basically bought

everything up. It’d be like one guy coming in and buying all the

newspapers in the country so you just had one big newspaper.”

The consolidation of the wrestling industry has drained much of its

color and personality, in Bourne’s opinion. He notes that during the

heyday of Mid-Atlantic Championship Wrestling, Greensboro would host 18

to 20 wrestling events; in contrast, the Greensboro Coliseum has booked

two WWE shows for 2006, booking manager George Scott says.

“Triple H, Kurt Angle and even Ric Flair today have been at the same

spot on television for three or four years and it gets a little stale,”

Bourne says. “There’s no new angles. There’s nowhere else for wrestlers

to learn their craft. [Before] there was no national promotion. All the

promoters worked together and respected each other’s territories. When

your character got stale you could move on to Georgia and Florida, and

those guys could come here.”

South winces when he thinks about his kids watching WWE wrestling on TV.

It’s the parade of half-naked women, the fact that the good guys often

curse so much you can’t tell them from the villains. It’s the lack of

care taken in creating believable storylines, like how a wrestler will

get run over by a car one day and be back in the ring the next. It’s the

stunts like blowing up the ring instead of focusing on good wrestling.

He points to wrestlers like Gorgeous George, a grappler who got started

in the ’50s, as exemplars of a lost art.

“He had this golden hair,” he says. “He was ahead of his time. People

wanted to come boo him. He’d say all those hard-working farmers were

dirty, so he’d have his male valet spray perfume in the ring before he’d

step in it. He’d go to every beauty parlor in town to have his hair

done, and invite the press to come along. By the time he got to the

Greensboro Coliseum we’d want to kill him.

“It don’t matter how tough we are,” he adds. “If we can’t entertain we

don’t have nothing.”

As a teacher South often finds himself frustrated by students who would

rather act tough than put on a good show. They fail to realize the

dramatic value of taking a humiliating beating to set the stage for a

triumphant reversal.

“Why would anyone get in this business and not know what they were

supposed to do?” he asks. “That’s the question of the ages.”

The wrestlers who keep audiences on the edge of their seats know how to

make each other look good, South says. The 44-year-old Brad Armstrong is

one of these. Armstrong is typecast as a good guy — or a babyface, in

wrestling parlance.

“You hit him, he’ll go down on his knee and a teardrop comes out of his

eye, and he’s looking at the audience like, ‘Please help me,’” says

South, who consistently plays the villain, or heel.

South’s finishing move is the claw. In a typical move South tries to

grip Armstrong’s head with a black glove given to him by Blackjack

Mulligan, a Texas wrestler now retired in Florida. Armstrong in turn

grabs his arm to fend him off.

“I’ll let Brad get up to his feet, and the whole crowd jumps to their

feet because they want to see him get loose — he’s balled up his fist —

and then I’ll crank back up,” South says. “Everybody sits down again and

they’re so mad. I’ve got the claw on him and he’s going limp. Then he’ll

slowly regain his strength and he’ll hit me. All of a sudden I’m waving

around like crazy.

“Sometimes, I’ll try to grab him in the ring and he’ll duck, and my hand

will clamp down on the rope,” he adds. “I act like I’m stuck. The ref is

trying to pull me off. That’s what you do to build up.”

As the old wrestling tradition fades, South looks back at the legacy of

his profession with circumspection. While many of his peers have

succumbed to drug abuse and womanizing, South has gravitated towards

religion. He transports a mobile ring on trailer to churches across the

Carolinas.

“A lot of these guys have made more money than you can imagine, but

they’re left with nothing.” South says. “If you’d have told me we’d take

a ring out to the churches when I was first getting started I never

would have believed you. I get ten to fifteen minutes to say what’s

important in the world, and that’s my relationship with the Lord.”

Circumstances have not been kind to many others in the profession.

“If we all OD’d in a motel room it’s like it’s normal, but being a

Christian is considered strange,” South says. “Jake ‘The Snake’ Roberts

said, ‘I’m gonna try to do better,’ and everybody laughed at him and

said he was faking. A lot of us church-going folks dropped the ball. We

should have come out and supported Jake.”

Roberts, a WWE legend, reportedly wrestles independently now and has

struggled with alcohol and drug addiction.

“We’ve had sixty guys die in the last few years, the legends of

wrestling,” South says. “Ninety-five percent of them was drugs, alcohol,

the steroid use. Their hearts just got too big.”

He mentions WWE wrestler Eddie Guerrero, who died on Nov. 13 at the age

of 38. Rip Hawk, who survived into his eighties and died a couple years

ago, according to South. Wahoo McDaniel who died in 2002 at the age of

64.

“It’s a hard, hard business,” South says. “I wish there were a lot of

happy endings and there’s not. Wahoo wrestled fifty years and died alone

in a hospital. Was that happy? Wahoo, on his deathbed, he was so mad

because the promoters that he worked with didn’t call him.”

If it’s true that opportunities for new talent trying to break in have

diminished with the consolidation of the industry, it could also be said

professional wrestling hasn’t provided much of a retirement plan for its

best talent.

“These old wrestlers can’t get a job as a greeter at Wal-Mart, but

they’ve traveled around the world, and met presidents and dictators,”

South says. “I’ve really looked from the outside in. So many of my

friends have died. It’s put a lot of things in perspective for me. You

may not make money, but you go out in that building and you give people

a good show.”

There’s one common thread between the showmen like Gorgeous George, the

exhilarating matches in regional centers like Greensboro and the oiled

machine that is professional wrestling today, as far as George South is

concerned.

“Flair is the last,” he says. “If Flair ever quits he’s the last of the

era.”

To comment on this story, e-mail Jordan Green at

jordan@yesweekly.com

Original link:

http://www.yesweekly.com/main.asp?SectionID=18&SubSectionID=44&ArticleID=834

|