|

MAIN PAGE

APPEARANCES

GEORGE'S PICS

GEORGE'S BIO

PRESS ROOM

GEORGE'S STORE

CONTACT GEORGE

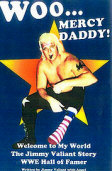

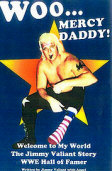

Check out Jimmy Valiant's

hot new book!

Woo...Mercy Daddy!www.JimmyValiant.com

|

|

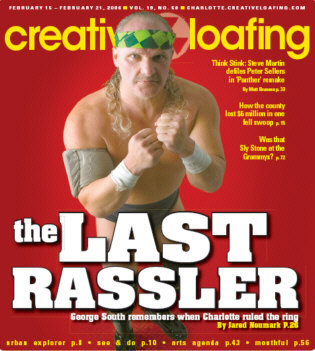

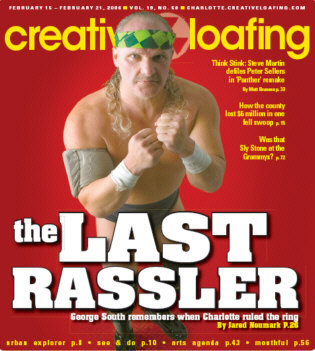

PRESS ROOM - CREATIVE LOAFING

MAGAZINE

FEBRUARY 15, 2006

Creative Loafing Magazine

Charlotte NC

Article by Jared Neumark, Photos provide by

the Mid-Atlantic Gateway

The Last Rassler

George South remembers when Charlotte ruled the ring

BY JARED NEUMARK

Published 02.15.06

This story features excerpts from Tony Earley's "Charlotte"

The professional wrestlers are gone. The professional wrestlers do

not live here anymore. Frankie Belk sold Southeastern Wrestling Alliance

to Ted Turner for more money than you would think, and the professional

wrestlers sold their big houses on Lake Norman and drove in BMWs down

I-85 to bigger houses in Atlanta.

Gone are Dusty Rhodes, the son of a plumber from Austin, TX, and the

Andersons, Gene and Ole, whose Anderson block would leave an exhausted

opponent marooned in the ring to flounder and drop like an animal shot

with a tranquilizer gun; gone are the tough guys, Chief Wahoo McDaniel,

who sewed his own stitches -- more than 2,000 in his career -- and

Johnny Valentine, who hit guys so hard that even the old-timers, who

never griped about anything, would complain. Gone are the Rock & Roll

Express, The Masked Superstar, Mr. Wrestling I and II, The Professor,

The Butcher, and Ricky Steamboat, the only wrestler who never turned bad

and couldn't, even if they gave him a chain saw.

Gone is the Iron Sheik, who brought a mat to pray to Allah before every

match -- to the boos of red-blooded Americans; gone is the Russian

Nightmare, Nikita Koloff, whose cold, angry stare could frighten a

marine even after the Cold War; gone are the flying elbows, airplane

spins, Superfly Splashes, brainbusters, Indian grapevines, Russian leg

sweeps and cobra holds; the midgets and giants, cowboys and Indians, the

Nazi sympathizers and Abe Jacobs the Jew.

Some are dead, some have fled Charlotte and some have settled into

anonymity. All but one, the most passionate wrestler who ever lived --

George South. If only this were a battle royal.

George has always had faith -- blind faith -- faith that won't submit to

a sleeper hold. His gospel is tattooed on his forehead and printed

across his chest. Between his faded blue eyes and his shoulder-length

gray hair (which he wore in a mullet in the golden 1980s), George's

forehead looks as if someone has played tic-tac-toe on it with a knife.

In extreme matches, wrestlers conceal razors in their wrist tape and,

during the bout, slice themselves along their foreheads. Their

blood-coated faces help sell the violence of the sport. Bulldog, one of

George's current students at his training school, says there was a time

when George cut himself every night.

George wears his other testament on T-shirts that he's diced into

midriff-sized, sleeveless rags. "I Love Jesus," "Jesus, That's My Final

Answer," and other religious messages hang over his undershirt like a

sandwich board or a bib. George began cutting his T-shirts because he

stained them all eating in his car on the road. Then he started to like

the style. He wears them everywhere -- to practice, around town, to

shows.

Question either of his two loves -- rasslin' or religion -- and you'll

set George off. He's easily excitable. When he's driving home a point,

he'll clap his hands three times or squeeze your shoulder. There's one

sure-fire way to get him worked up, but don't you dare try it. Don't you

dare to say that four-letter f-word: F-A-K-E.

If you didn't follow wrestling, you wouldn't understand. You'd see them

throw punches intended to miss, you'd see choke holds that don't really

choke. You might call it phony, but you'd be missing the point.

"Why would anyone want to know if it's fake? You're not going to be

better off," says George. "I still believe in Santa Claus and the Easter

Bunny. To this day I don't want to know how a magician pulls a rabbit

out of his hat."

In the old days in Charlotte we did not take ourselves so seriously.

Our heroes had platinum blond hair and twenty-seven-inch biceps, but you

knew who was good and who was evil, who was changing over to the other

side, and who was changing back. You knew that sooner or later the

referee would look away just long enough for Bob Noxious to hit Lord

Poetry with a folding chair. You knew that Lord Poetry would stare up

from the canvas in stricken wonder, as if he had never once in his life

seen a folding chair. (In the bar, we screamed at the television, Turn

around, ref, turn around! Look out, Lord Poetry, Look out!)

The old days started in 1934 when a soft-spoken man came down from the

Virginia mountains to Trade and Tryon streets with a vision and $5,000

in his pocket. Big Jim Crockett, as he came to be known, wasn't

nicknamed in the ironic sense. He was big. He kept a towel on the

dashboard of his car and would put it between his gut and the steering

wheel to keep the two from touching when he drove.

Crockett promoted everything in Charlotte. He brought in the big bands

of the 1930s and 1940s and rock and country in the 1950s and 1960s. He

was friends with Gene Autry and James Brown. Popular musicals such as My

Fair Lady came through town because of him. Even though he struggled to

make money with the musicals, it didn't matter. He thought Charlotteans

should have a chance to see them. Paul Buck, a manager of the old

Charlotte Coliseum during wrestling's early-1970s heyday, credited

Crockett alone with keeping the place in business.

But Big Jim's passion was for the men whose fates he controlled as if he

were a god. He obsessed over his wrestling league. He answered most

calls that came into his Morehead Street office. If a fan called in to

talk to a wrestler, Crockett knew which wrestler he should push harder.

On Jan. 11, 1958, his first televised match aired live from WBTV's

40-by-60-foot studio. Big Jim gave his show to the CBS affiliate for

free. In return, the hour-long program served as an advertisement for

bigger Monday night events at the Park Center, the cramped auditorium

that hosted wrestling well into the 1980s. The Park Center's low ceiling

stood only 10 feet below the top rope of the ring, and the rare times a

wrestler climbed up to the turnbuckles to leap off, it looked as if he

might fly right through the ceiling.

Before the TV broadcasts, Crockett, usually in a navy blue suit that

could carpet a den, would approach production manager Virgil Torrance to

tell him how many chairs he should set up for the segregated black

audience. The wrestlers took pleasure in scaring the black children, and

Torrance tried to get them to stop. Almost every week he had to clean a

small pool of urine the terrified tykes would leave behind.

The show never went a second over the time cap. Crockett sat on a

platform perched over his wrestlers and when he felt the match had gone

on long enough, he would raise his hand slightly above his head, like a

Roman emperor. Within seconds someone was down for a three count.

In the early days there were less gimmicks and less muscles. There were

good guys and bad guys, and maybe an Indian. To set off a crowd, all it

took was an illegal yank of the hair or a tug of the trunks.

In the old days in Charlotte we did not have to decide whether the

Hornets should trade Rex Chapmen (they should not) or if J.R. Reid was

big enough to play center in the NBA (he is, but only sometimes). In the

old days our heroes were as superficial as we were -- but we knew that

-- and their struggles were exaggerated versions of our own.

Wrestling wasn't born in Charlotte, but it flourished here. Before Vince

McMahon won the race to syndicate his promotion nationally, before there

even was a race, promoters protected their territories like the Bloods

and Crips. Professional sports teams were few and far between south of

the Mason-Dixon, and wrestling's squared circle filled the void. In the

1970s, the general consensus was that up north, wrestling was fake, but

down here, rasslin' was for real.

Among Southern territories, Crockett's Mid-Atlantic became the center of

activity. Other territories had their moments. In the earlier 1970s, the

Brisco brothers, Paul Jones and announcer Gordon Solie (the Walter

Cronkite of wrestling) propelled Championship Wrestling from Florida to

the center of the wrestling world. Memphis had Jerry Lawler. Fritz Von

Erich, a Texan wrestling as a Nazi, started a Reich out of wrestling's

most famous venue, the Sportatorium, in Dallas. Fritz' World

Championship Wrestling used six cameras, three more than any other

promotion at the time. He sold his show to Japan and Israel, becoming

the first promoter to syndicate internationally. Fans of Georgia

Championship Wrestling stood up to McMahon on Black Saturday, when

without warning one evening in 1984, McMahon's northeastern-based World

Wrestling Federation replaced the good ol' Georgia boys on TBS. The

fans' letter-writing campaign and boycott convinced network owner Ted

Turner to change his mind and keep the local product.

But Charlotte was the capital of Southern rasslin'. Other territories

were too small for many wrestlers to make it big; only a few at the top

could rake in the money. In Crockett's Mid-Atlantic territory there were

plenty of shows, all within a reasonable driving distance from each

other. Big-name wrestlers were on a waiting list to get into the

Charlotte-based territory. The Mid-Atlantic stretched from Charleston in

the south to Richmond up north, from Toccoa, GA, to the west and east to

the ocean. In the Mid-Atlantic, according to Boogie Woogie Man Jimmy

Valiant, Crockett had his boys working nine times a week (twice on

Saturday and Sunday). On a good night, three shows employing up to 50

wrestlers ran across his vast region.

Big Jim's girth caught up to him. He died of a heart attack in 1973 and

his oldest son, Jim Crockett Jr., took over. Little Jim shared his

father's taciturn manner, but not his passion for the sport. When he

inherited the company, Little Jim made two major changes that fueled the

wrestling boom here. Charlotte had been known as a tag-team territory,

but Jim realized the marketability of the individual wrestling star. He

hired George Scott, a former wrestler and mastermind at creating story

lines and angles, as a booker. Scott brought in guys with charisma, such

as Chief Wahoo from Minnesota, who a year later would convince an

unproven brash youngster, Rick Fliehr, to join him down south. Fliehr

became Nature Boy Ric Flair.

On Saturdays in 1978, 106,000 homes in the Charlotte area tuned in to

watch Mid-Atlantic wrestling. It outrated The Wide World of Sports, NCAA

football and NCAA basketball. In Greensboro, wrestling did better with

adult males than Starsky and Hutch or Kojak. Mello Yellow printed images

of Ric Flair, Paul Jones and other warriors on the backs of cans; gas

stations carried cups with the wrestlers on them. John Cougar Mellencamp,

facing empty seats one night in Charlotte, opened his concert by saying

it was a shame the Rock & Roll Express, a tag-team of fake rock stars,

drew a bigger crowd than his.

The average wrestling fan was lower to middle class in the beginning.

But as with NASCAR, wrestling eventually became the "in" thing to

follow, says longtime fan Michael Bochicchio, who runs a wrestling

Internet store off Eastway Drive. During its heyday, people in Charlotte

talked about wrestling like they talk about the Panthers today.

Story lines in wrestling are called angles. In the old days, angles were

drawn out over years. A big match could be the culmination of years of

backstory. Ric Flair's rivalry with Ricky Steamboat spanned ten years.

Some angles included drastic consequences. In one scenario, if Dusty

Rhodes defeated Tully Blanchard, Rhodes would win the services of

Tully's blonde, buxom manager, Baby Doll, for 30 days. (The services

implied went beyond managerial expertise.) Longtime partners Jay

Youngblood and Ricky Steamboat fought one match under the condition that

if they lost, they could never tag together again. Prior to pay-per-view

TV, the only way to see big events such as this one was in person.

Traffic on US 85 going into Greensboro backed up to a standstill.

The bookers often used racially charged characters and story lines.

During the Iranian hostage crisis, the Iron Sheik became world champion.

In one famous angle, Flair and the Andersons jumped Rufus Jones outside

the ring and forced him to wear a chauffeur's cap. No one apologized.

These angles put fans in the seats. People wanted to see bad guys like

Flair get what was coming to them.

On nights when the crowd gave up extra heat, the wrestlers would

continue to fight all the way back to the locker rooms. Without

barricades, it wasn't safe for the bad guy to be among angry fans. Mobs

slashed Ric Flair's tires in the parking lot so often that he started

driving junk cars to the arenas. On occasion, the crowd heat turned

violent. In Greenville. SC, one night, a 79-year-old man stabbed Ole

Anderson, slicing open his stomach like a fish's. Anderson, lucky to

have lived, spent the day recovering in Charlotte's Memorial Hospital.

But 24 hours later, he was in Raleigh for a studio taping.

Wrestlers refer to gullible fans as marks. As a kid growing up in

Gastonia in the 1970s, George was the definition of the term. He stayed

home from school for three days when his hero, Paul Jones, lost the belt

to Blackjack Mulligan. If someone saw Ric Flair at a Waffle House,

George would stake it out for weeks hoping to catch a glimpse of him.

George watched a TV interview with the Andersons after they won their

world championship belts. When he saw them toss their less prestigious

regional belts in the garbage, George and his friends scoured dumpsters

across the city looking for them.

His heroes didn't hide in Ballantyne mansions. Paul Jones had a garage

on Central Avenue. Boogie Woogie bought a flower shop on South Boulevard

for his frizzy haired wife and ringside manager, Big Mama. Anyone could

go into Big Mama's Flowers, find Boogie there and get an autograph. Gene

Anderson, who was so mean he didn't talk during interviews, loved

children and owned a putt-putt and arcade on Independence Boulevard by

the old coliseum. Nelson Royal ran a ranch and Western store in

Mooresville. Ricky Steamboat hand-built the weights for his gym on

Harris Boulevard. Jay Youngblood, Steamboat's tag-team partner and best

friend, ran a juice bar inside the gym. When they wanted to relax or get

something to eat, the boys hung out at Bennigans, a fake Irish

restaurant.

I manage a fern bar on Independence Boulevard near downtown, called

P.J. O'Mulligan's Goodtimes Emporium. The regulars call the place P.J.'s.

When you have just moved to Charlotte from McAdenville or Cherryville or

Lawndale, it makes you feel good to call somebody up and say, Hey let's

meet after work at P.J.'s. It sounds like real life when you say it, and

that is a sad thing. P.J.'s has fake Tiffany lampshades above the

tables, with purple and teal hornets belligerent in the glass. It has

fake antique Coca-Cola and Miller High Life and Piece-Arrow automobile

and Winchester Repeating Rifle signs screwed into the walls, and

imitation brass tiles glued to the ceiling. (The glue occasionally lets

go and the tiles swoop down towards the tables, like bats.) The ferns

are plastic because smoke and people dumping their drinks on the

planters kill the real ones. The beer and mixed drinks are expensive,

but the chairs and stools are cloth-upholstered and plush, and the

ceiling lights in their smooth, round globes are low and pleasant

enough, and the television set is huge and close to the bar and

perpetually tuned to ESPN.

At 17, George responded to a newspaper ad looking for wrestlers. Most

people would call it a scam. George wouldn't be making money; he had to

pay the promoter to let him wrestle. It was the only way to get

experience. For exposure, he mailed out fliers and pictures to bigger

promotions around the country. One day, in 1980, Georgia Championship

Wrestling in Atlanta called him up and gave him a shot. Then Jim

Crockett found out George was living in Concord, and he gave him a shot,

too.

George was a jobber. Among the boys in the business, the word is

practically a slur. The jobber's role is to lose matches in order to

make his opponent, usually a headliner, look better. They would put

George in masks. One night he wrestled in royal blue as one of the

Gladiators. The next night he'd be with the same tag-team partner, but

this time wearing neon green and billed as the Cruel Connection. The

night after, he was a Mexican Twin Devil. Other times George wrestled as

himself. On a few occasions he wrestled two matches on the same card.

Even the Crocketts couldn't keep it straight.

Unlike a headliner, George couldn't rely on regular bookings. He took

side jobs -- mowing lawns, flipping burgers at McDonald's, doing any

menial task you can think of -- but he tried to hide it from the other

wrestlers. He got to the arenas early to shower and wash the stench of

chicken grease off his body.

Still, George was thankful. It didn't matter if he had one match or ten,

every week he called the Crockett office to thank him for the work. It

got to the point where the secretary finally said, "George, he knows

you're thankful. Leave us alone." Still, George would call.

Partying came along with the fame. Rats (wrestling's version of

groupies) followed the wrestlers from town to town. In Ric Flair's

autobiography, To Be the Man, he writes of wild parties in Charlotte.

But George wouldn't participate in the revelry: "Why would I go get

plastered when I can ask Gene Anderson what did Ole do the night an

80-year-old man opened him up?"

The big-name wrestlers took care of George. Flair and some of the others

had contests to see who could tip George the most for running errands.

He would get $20 for picking up a $3 sandwich.

At a TBS match in Atlanta, George fought against Devil Blue, a grouchy

old-timer who wouldn't reveal his identity even in the locker room. He

showered in his mask and drove away from the arena wearing it. Devil

Blue lifted George, turned him upside down and slammed him into a belt

buckle. George went numb. Some of the wrestlers carried him backstage,

and while he waited for an ambulance, Flair walked by and slipped $50

into his hand. It was Flair's way of saying he cared.

Some old-timers saw George coming and would turn away, knowing he was

about to attack them with an arsenal of questions. He lived for eating

steak with Ricky Steamboat or splitting a motel with Flair, but George's

favorite times were late at night on empty interstates, with the

headlocks left behind in Portsmouth or Columbia, and when his heroes in

the passenger seats dropped their macho gimmicks and became regular

people.

About once a week some guy who's just moved to Charlotte from Kings

Mountain or Chester or Gaffney comes up to me where I sit at the bar, on

my stool by the waitress station, and says, Hey, man, are you P.J.

O'Mulligan? They are never kidding, and whenever it happens I don't know

what to say. I wish I could tell them whatever it is they need in their

hearts to hear, but P.J. O'Mulligan is fourteen lawyers from Richmond

with investment capital. What do you say? New people come to Charlotte

from the small towns every day, searching for lives that are bigger than

the ones they have known, but what they must settle for, once they get

here, are much smaller hopes: that maybe this year the Hornets might

really have a shot at the Celtics, if Rex Chapmen has a good game; that

maybe there really is somebody named P.J. O'Mulligan, and that maybe

that guy at the bar is him. Now that the wrestlers are gone, I wonder

about these things. How do you tell somebody how to find what they're

looking for when ten years ago you came from the same place and have yet

to find it yourself? How do you tell somebody from Polkville or

Aliceville or Cliffside, who just saw downtown after sunset for the

first time, not to let the beauty of the skyline fool them?

Today, the new people in Charlotte come from bigger towns: Los

Angeles, Atlanta, New York. They come here with their new husbands or

wives, and if they didn't bring a partner, they find one here. They come

to hedge mutual funds and to watch Golden Jake, the quarterback with a

decent arm and spastic feet, throw one ball too many to the wrong team.

What killed wrestling in Charlotte? Pick something. Little Jim Crockett

couldn't compete with the shrewder Vince McMahon. Instead of staying in

the mid-Atlantic region, Jim played Vince's game, invested all his

profits in expansion and got burned. Jim also entrusted too much power

to his booker, Dusty Rhodes, who cared more about promoting himself than

the business. Dusty ran expenses through the roof.

Wrestlers took limos and airplanes everywhere. When Crockett bought a

second plane during his expansion, the wrestlers would sometimes fly it

just to go from Charlotte to Greensboro. When contracts were introduced

in the 1980s, wrestlers for the first time got hefty yearly salaries

instead of having to bust their tails every night. The sport lost its

shock value. To compete with a blossoming entertainment industry,

bookers pulled more and more outlandish angles. Who would believe a

piledriver hurt when guys were being set afire?

Charlotte is a place where a crooked TV preacher can steal money and

grow like a sore until he collapses from the weight of his own evil by

simply promising hope. So don't stare at the NCNB Tower against the dark

blue sky; keep your eyes on the road. Don't think that Independence

Boulevard is anything more than a street. Most of my waitresses are

college girls from UNCC and CPCC, and I can see the hope shining in

their faces even as they fill out applications. They look good in their

official P.J. O'Mulligan's khaki shorts and white sneakers and green

aprons and starched, preppy blouses, but they are still mill-town girls

through and through, come to the city to find the answers to their

prayers. How do you tell them Charlotte isn't a good place to look?

A sane man would have ridden off into the sunset when the wrestlers left

town. They've gone from packed arenas in Greensboro and Charlotte to

half-empty armories and recreation centers in Albemarle and Elkin. Shows

are cancelled with little warning when promoters realize ticket sales

won't cover expenses. Between February and April, wrestling activity

flurries as poor promoters become optimistic with tax refunds.

Still, George holds out hope that a renaissance is around the corner. He

trains kids with similar dreams who come to Charlotte from all over.

David Flair, Ric's son, trains with George. The Guerreros moved here

from California when they saw an ad in a wrestling magazine. Bulldog,

from Canada, can only stay in the US for three months at a time, and

this is his third go-round. Many of these wannabe pros intern with

George's partner, Mike Bochicchio, at his Internet wrestling superstore

in exchange for a room, a small stipend that doesn't go far beyond fast

food and free training with George.

Vince McMahon's national promotion, WWE, dominates the professional

wrestling scene. It's nearly impossible for a wrestler to get noticed,

and even then, the WWE tends to take only guys in the mold of the

Incredible Hulk. "My main regret for these new guys is they don't really

have anywhere to go. It's sad," says Mike Cline, a fan who has followed

wrestling in Charlotte since the 1960s.

George runs shows for his Exodus Wrestling Alliance anywhere he can. His

most regular gig is for mentally ill children at a group home in

Morganton. Wheel chairs and beds surround George's ring, and the home

doesn't pay. But George takes the job because it's valuable ring

experience for his students and he wants to teach them the Christian

principle of doing selfless acts. The group home residents are George's

most enthusiastic audience.

Sometimes in the same week, George's students will drive to a strip club

in Atlanta to perform while surrounded by naked women giving lap dances

to men. Unlike the crowd at the group home, here no one pays attention

to the wrestling. George also has done free shows in prisons and outside

the Speedway during racing weekends. On the road, George's EWA cuts

costs by putting up to nine wrestlers in a motel room. Other times they

sleep in cars.

At the EWA's church shows, swearing and low blows are prohibited. In an

angle George did at a church, one wrestler was about to throw another

wrestler through a table, but a third, playing the role of Jesus,

stepped into the ring and sacrificed himself to go through the table

instead. After these matches, George shares his personal testimony.

Today, old-style wrestling has lost much of its respect. When George

prays in locker rooms, his own guys interrupt him by coughing

intentionally or unzipping their bags back and forth. With fans, it's

even worse. Last year George opened for Puddle of Mudd at a show that

also promised midget wrestlers. In the opening bout, while George

sparred against a taller opponent, the crowd got impatient. Beer bottles

came raining down, and George had to take shelter under the ring.

Sometimes, in the middle of matches, fans chant "boring." Other fans

walk up to George just to tell him he's a phony.

"My dream in my perfect little world that my wife says I live in is that

Jim Crockett is going to come back, start all over and do this again,"

says George. "I know things have changed and I ain't getting any

younger. But who knows? It just can't end like this."

Those were glorious days. Whenever Rockin' Robbie walked into P.J.'s,

everybody in the place raised their glasses and pointed their noses at

the fake bronze of the ceiling and bayed at the stars we knew spun, only

for us, in the high, moony night above Charlotte. Nothing like that

happens here anymore. Frankie Belk gathered up all the good and evil in

our city and sold it four hours south. These days the illusions we have

left are the small ones of our own making, and in the vacuum the

wrestlers left behind, those illusions become too easy to see through;

we now have to live with ourselves.

* * * * * * * *

Italicized sections are excerpts from Tony Earley's short story

"Charlotte," originally published in 1992 in Harper's Magazine. Earley

is the author of the collection Here We Are in Paradise, in which

this story appears, and the novel Jim the Boy, both available on

Amazon.com. He is currently at work on a sequel to Jim the Boy.

Original Link:

http://charlotte.creativeloafing.com/gyrobase/Content?oid=oid%3A7426

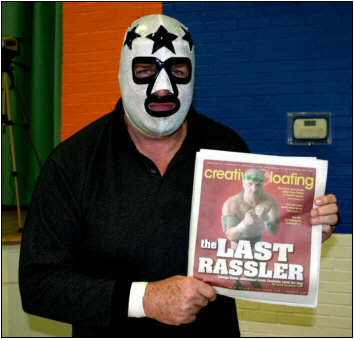

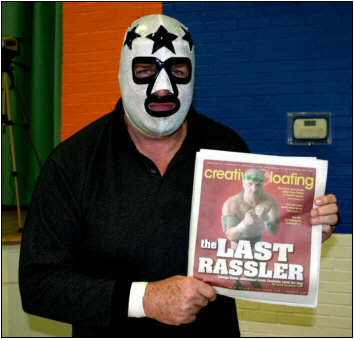

The Masked Superstar Bill Eadie holds the Feb. 15th

issue of Charlotte's Creative Loafing magazine.

The issue features George South on the cover.

(Shelby NC 2/17/06)

(Photo by Dick Bourne)

|